Perspectives from Contributing to Angular

The Angular framework is easily the largest and most complex codebase I have worked with, and has taught me valuable ideas about software development. This post discusses what I’ve learned about understanding and working on large codebases, and how my confidence in open-source contribution has changed since working on Angular. If you’re interested in the technical aspects on my work, I’ve discussed them in another article.

Views from Above

Having done even a small amount of work with the Angular compiler, I’ve found that it’s often best to look at the big picture when contributing to a large project.

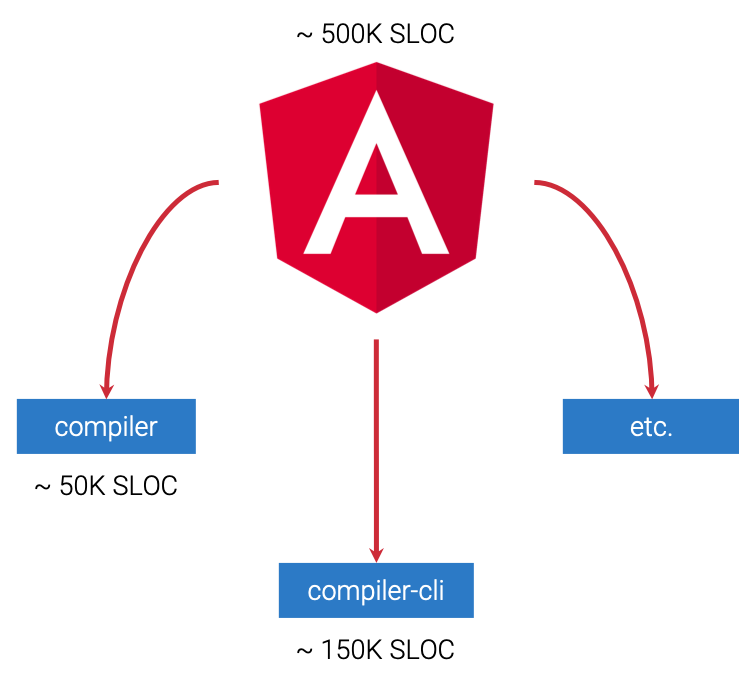

Sizes of packages in the Angular framework

Angular is a tremendous endeavor — discounting the Angular CLI or Angular components, the Angular framework on its own is on the order of 500K source lines of code. For context, Chromium is nearing 5MM SLOCs, and Rust’s rustc compiler is around 700K SLOCs.

A large part of the Angular framework doesn’t affect apps built with Angular; much of it is devoted towards building a good development experience, documentation, and common libraries. The main idea, though, is that it’s difficult to deeply understand all of the framework and make a product that consumes it in three months.

Rather than trying to understand everything, attention must be focused on the parts of the project that affect and rely on the new integration in the product. The question then becomes how to focus one’s attention on this, which in a large codebase can be very daunting.

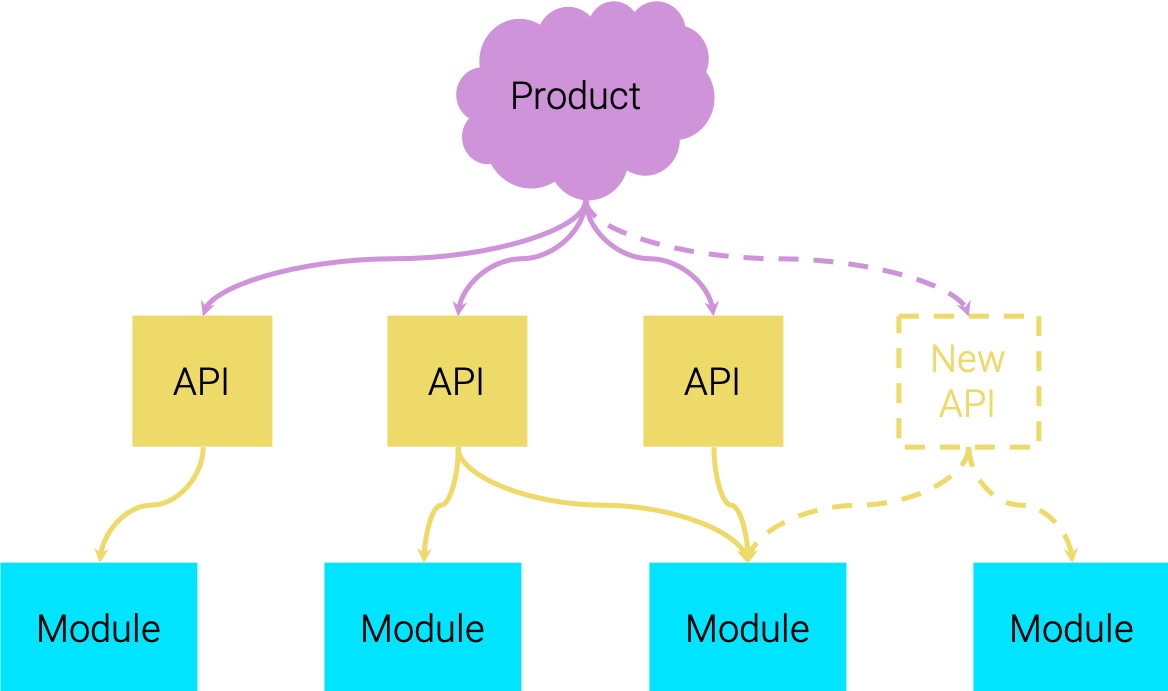

As I worked on installing a new API in the Angular compiler, I began to imagine it as a stack of at least three layers:

Angular compiler layers

- The product layer, consisting of the compiler as a whole.

- The API layer, providing APIs consumed by the product.

- The module layer, consisting of smaller code units consumed by APIs.

A new API thus both consumes some modules and itself is consumed by the product.

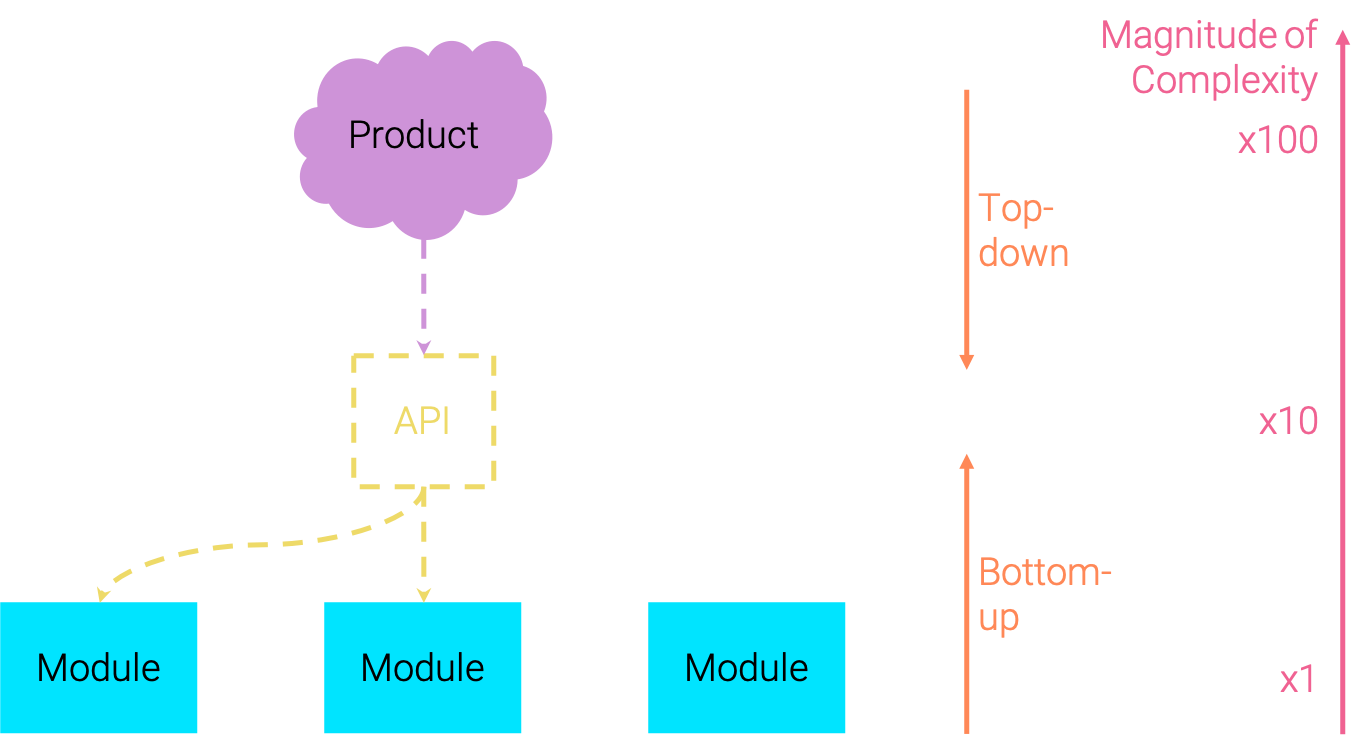

Magnitude of complexity in understanding various layers

It’s interesting to consider the complexity of each layer. In my opinion, the magnitude of complexity in understanding what something at each layer does increases towards the top of the layer tree. It might be very easy to understand the logic encapsulated in an individual module, but understanding all the logic encapsulated in the consumers of modules is much harder; for an API that uses multiple modules, it may be something like 10x more complex, and for the entire product it may be 100x more complex. These are rough numbers, but the idea stands.

Given this, consider some new, formalized API specification. There are at least two strategies to figure out how to implement this API:

- Top-down: start from the product layer and look down to see where the API should be plugged in.

- Bottom-up: start from the module level and look up to see what modules need to be combined for the API.

The difference between these two approaches is top-down divides complexity of understanding; bottom-up magnifies complexity. Lower levels of abstraction generally shouldn’t know about higher levels of abstraction; trying to do so multiplies the complexity of a lower-level abstraction. But because a high-level abstraction is all-encompassing, the complexity (and mental model) of an abstraction is cleaved looking from the top.

In the end, both directions will in arrive at the same level of complexity; the getting there is what makes the difference. I’m not convinced it’s always the best approach, but for a large codebase like the Angular compiler I’ve found the top-down approach to be significantly easier in making decisions about integrations.

Of course this is a nuanced conclusion, but I think it’s a generally reasonable guideline for large projects, which experience effects of scale. In a small project, it might be easy to change something in a module, then bubble that change up through the API and product layer. But this is often difficult in a large project, where a lot of moving pieces make it so that it is often easier to first derive a holistic implementation plan by understanding what role a module plays in the whole product.

In the end, both directions will in arrive at the same level of complexity; the getting there is what makes the difference.

Fitting Shoes

Aside an approach to development, my work on the Angular compiler taught me something about approaching unfamiliar projects. I talk about open-source software projects here, but this is generally applicable to any kind of project.

Projects manifesting a contributor’s identity

I think of open-source projects kind of like shoes that a contributor wears. There at least two factors considered when an individual chooses what shoe to wear:

- Style match — whether the shoe has a style suiting the individual.

- Accessibility match — whether the shoe physically fits the individual.

Open-source projects are similar to shoes in these considerations. A contributor wants to be interested in a project and help develop it, and also has to find development of the project accessible — that is, a contributor prefers projects that are easier to ramp up on and have a network of resources.

Contributing is difficult. It’s difficult to look at something one knows nothing about, figure out how it works, and then augment it to do something different or new. Given enough time, this can always be done, but no one ever has enough time. So for a contributor considering investing effort in a project, the decision often comes down to a consideration of the project’s style and accessibility match.

I have thought about how to make projects more accessible to others; there are many who have studied this question more and have much better answers than I do, but perhaps one of the most important answers is developer documentation. Great code comments and written documentation describing project implementations make it much easier for a contributor to begin creating a mental model. This is even more valuable than having a code author by the contributor’s side, because authors forget or leave to do other things, but documentation stays forever.

Contributing is like riding a bike

The other thing is for me, at least in some sense, contributing is a skill. Over time, my perception of contribution has lost its sense of inherent difficulty and intimidation. I now find it relatively easy to open up another open-source project and hack on it to do something I want it to do. Alongside being a consequence of my improvement as an engineer, I think this is a result of some intuition for contribution I’ve built up. It’s difficult to explain what exactly there is to it, but like riding a bicycle, it’s just there and it’s difficult to forget.

For me, this intuition is great because while it still may be challenging to enter a new community or introduce a large change, having some general knowledge of where to start in doing these kinds of things goes a long way towards improving confidence in one’s contributions. This is the most important thing, because contributors should be valued.

Those are some of my experiences and thoughts, anyway. I hope they can provide a perspective.

Suggest:

☞ Angular Tutorial - Learn Angular from Scratch

☞ Angular and Nodejs Integration Tutorial

☞ JavaScript Programming Tutorial Full Course for Beginners

☞ Learn JavaScript - Become a Zero to Hero