Node.js & JavaScript Testing Best Practices (2019)

The ideas below span topics like choosing the right test types, coding them correctly, measuring their effectiveness and hosting them in a CI/CD pipeline in the right way. Some examples are illustrated using Jest, others with Mocha — this post is less about tooling and more about the right approach and techniques.

My name is Yoni Goldberg, an independent Node.JS consultant and the co-author of Node.js best practices. I work with customers at the USA, Europe, and Israel on polishing their Node.js applications. Among my service are also test planning, test review, and CI/CD setup. Follow me on Twitter

Reviewed & improved by Bruno Scheufler

⚪️ 0. The Golden Rule: Testing must stay dead -simple and clear as day

Are you familiar with that smiley friend, family member or maybe a movie character who is always available to spare his good working hands, 24/7 assisting when you need him tuned with positive energy yet asking so little for himself? This how a testing code should be designed — easy, valuable and fun. This can be achieved by selectively cherry-picking techniques, tools and test targets that are cost-effective and provide great ROI. Test only as much as needed, strive to keep it nimble, sometimes it’s even worth dropping some tests and trade reliability for agility and simplicity.

Testing should not be treated as a traditional application code — a typical team is challenged with maintaining its main application anyway (the features we code and sell), it could not tolerate additional complex “project”. Should testing grow to be an additional source of pain — it will get abandoned or greatly slow down the development.

In that sense, the testing code must stay dead-simple, with minimal dependencies, abstractions, and levels of indirection. One should look at a test and get the intent instantly. Most of the advice below are derivatives of this principle

Section : The Test Anatomy

1. Include 3 parts in each test name

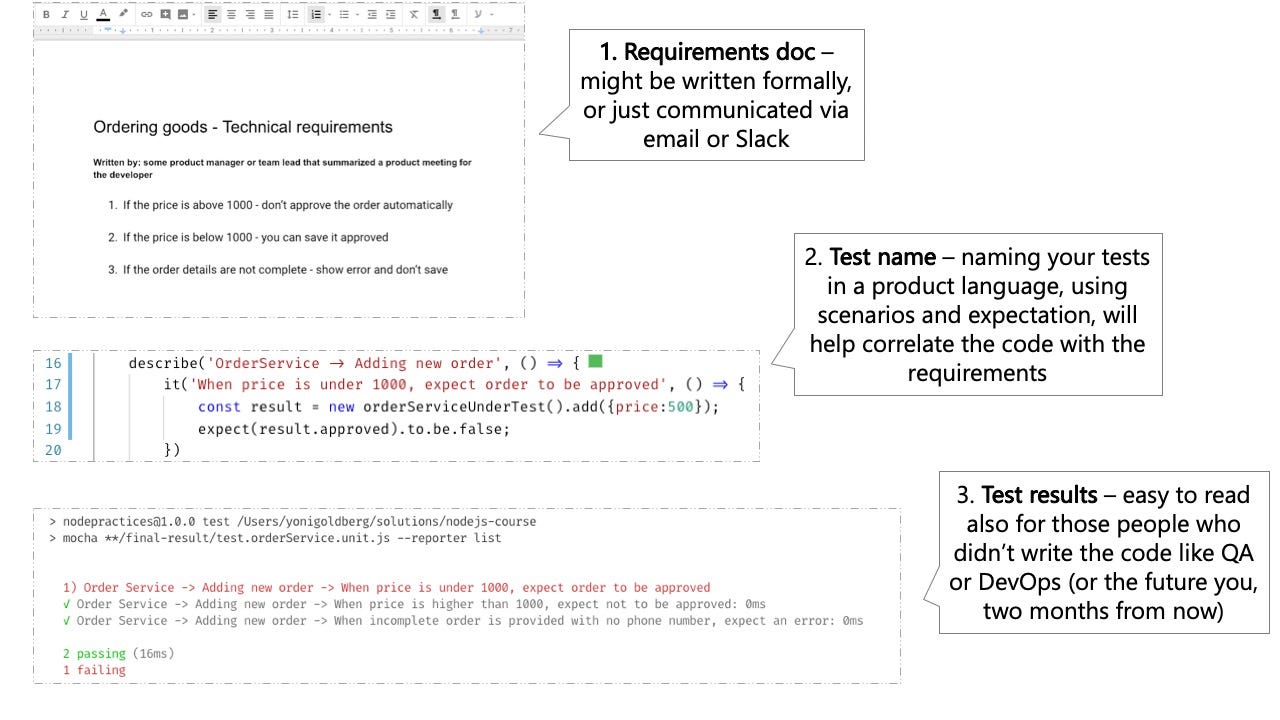

Do: A test report should tell whether the current application revision satisfies the requirements for the people who are not necessarily familiar with the code: the tester, the DevOps engineer who is deploying and the future you two years from now. This can be achieved best if the tests speak at the requirements level and include 3 parts:

(1) What is being tested? For example, the ProductsService.addNewProduct method

(2) Under what circumstances and scenario? For example, no price is passed to the method

(3) What is the expected result? For example, the new product is not approved

Otherwise: A deployment just failed, a test named “Add product” failed. Does this tell you what exactly is malfunctioning?

☺️ Doing It Right Example: A test name that constitutes 3 parts

3parts.js

//1. unit under test

describe('Products Service', function() {

describe('Add new product', function() {

//2. scenario and 3. expectation

it('When no price is specified, then the product status is pending approval', ()=> {

const newProduct = new ProductService().add(...);

expect(newProduct.status).to.equal('pendingApproval');

});

});

});

️Doing It Right Example: The test report resembles the requirements document

2. Describe expectations in a product language: use BDD-style assertions

Do: Coding your tests in a declarative-style allows the reader to get the grab instantly without spending even a single brain-CPU cycle. When you write an imperative code that is packed with conditional logic the reader is thrown away to an effortful mental mood. In that sense, code the expectation in a human-like language, declarative BDD style using expect or should and not using custom code. If Chai & Jest don’t include the desired assertion and it’s highly repeatable, consider extending Jest matcher (Jest) or writing a custom Chai plugin

Otherwise: The team will write less test and decorate the annoying ones with .skip()

Anti Pattern Example: The reader must skim through not so short, and imperative code just to get the test story

complex-assertions.js

it("When asking for an admin, ensure only ordered admins in results" , ()={

//assuming we've added here two admins "admin1", "admin2" and "user1"

const allAdmins = getUsers({adminOnly:true});

const admin1Found, adming2Found = false;

allAdmins.forEach(aSingleUser => {

if(aSingleUser === "user1"){

assert.notEqual(aSingleUser, "user1", "A user was found and not admin");

}

if(aSingleUser==="admin1"){

admin1Found = true;

}

if(aSingleUser==="admin2"){

admin2Found = true;

}

});

if(!admin1Found || !admin2Found ){

throw new Error("Not all admins were returned");

}

});

Doing It Right Example: Skimming through the following declarative test is a breeze

simple-assertion.js

it("When asking for an admin, ensure only ordered admins in results" , ()={

//assuming we've added here two admins

const allAdmins = getUsers({adminOnly:true});

expect(allAdmins).to.include.ordered.members(["admin1" , "admin2"])

.but.not.include.ordered.members(["user1"]);

});

view raw

3. Lint with testing-dedicated plugins

Do: A set of ESLint plugins were built specifically for inspecting the tests code patterns and discover issues. For example, eslint-plugin-mocha will warn when a test is written at the global level (not a son of a describe() statement) or when tests are skipped which might lead to a false belief that all tests are passing. Similarly, eslint-plugin-jest can, for example, warn when a test has no assertions at all (not checking anything)

Otherwise: Seeing 90% code coverage and 100% green tests will make your face wear a big smile only until you realize that many tests aren’t asserting for anything and many test suites were just skipped. Hopefully, you didn’t deploy anything based on this false observation

Anti Pattern Example: A test case full of errors, luckily all are caught by Linters

testing-lint-errors.js

describe("Too short description", () => {

const userToken = userService.getDefaultToken() // *error:no-setup-in-describe, use hooks (sparingly) instead

it("Some description", () => {});//* error: valid-test-description. Must include the word "Should" + at least 5 words

});

it.skip("Test name", () => {// *error:no-skipped-tests, error:error:no-global-tests. Put tests only under describe or suite

expect("somevalue"); // error:no-assert

});

it("Test name", () => {*//error:no-identical-title. Assign unique titles to tests

});

4. Stick to black-box testing: Test only public methods

Do: Testing the internals brings huge overhead for almost nothing. If your code/API deliver the right results, should you really invest your next 3 hours in testing HOW it worked internally and then maintain these fragile tests? Whenever a public behavior is checked, the private implementation is also implicitly tested and your tests will break only if there is a certain problem (e.g. wrong output). This approach is also referred to as behavioral testing. On the other side, should you test the internals (white box approach) — your focus shifts from planning the component outcome to nitty-gritty details and your test might break because of minor code refactors although the results are fine- this dramatically increases the maintenance burden

Otherwise: Your test behaves like the child who cries wolf: shoot out loud false-positive cries (e.g., A test fails because a private variable name was changed). Unsurprisingly, people will soon start to ignore the CI notifications until someday a real bug will get ignored…

Anti Pattern Example: A test case is testing the internals for no good reason

testing-the-internal.js

class ProductService{

//this method is only used internally

//Change this name will make the tests fail

calculateVAT(priceWithoutVAT){

return {finalPrice: priceWithoutVAT * 1.2};

//Change the result format or key name above will make the tests fail

}

//public method

getPrice(productId){

const desiredProduct= DB.getProduct(productId);

finalPrice = this.calculateVATAdd(desiredProduct.price).finalPrice;

}

}

it("White-box test: When the internal methods get 0 vat, it return 0 response", async () => {

//There's no requirement to allow users to calculate the VAT, only show the final price. Nevertheless we falsely insist here to test the class internals

expect(new ProductService().calculateVATAdd(0).finalPrice).to.equal(0);

});

️️5. Choose the right test doubles: Avoid mocks in favor of stubs and spies

Do: Test doubles are a necessary evil because they are coupled to the application internals, yet some provide an immense value (Read here a reminder about test doubles: mocks vs stubs vs spies). However, the various techniques were not born equal: some of them, spies and stubs, are focused on testing the requirements but as an inevitable side-effect they also slightly touch the internals. Mocks, on the contrary side, are focused on testing the internals — this brings huge overhead as explained in the bullet “Stick to black box testing”.

Before using test doubles, ask a very simple question: Do I use it to test functionality that appears, or could appear, in the requirements document? If no, it’s a smell of white-box testing.

For example, if you want to test what your app behaves reasonably when the payment service is down, you might stub the payment service and trigger some ‘No Response’ return to ensure that the unit under test returns the right value. This checks our application behavior/response/outcome under certain scenarios. You might also use a spy to assert that an email was sent when that service is down — this is again a behavioral check which is likely to appear in a requirements doc (“Send an email if payment couldn’t be saved”). On the flip side, if you mock the Payment service and ensure that it was called with the right JavaScript types — then your test is focused on internal things that got nothing with the application functionality and are likely to change frequently

Otherwise: Any refactoring of code mandates searching for all the mocks in the code and updating accordingly. Tests become a burden rather than a helpful friend

Anti-pattern example: Mocks focus on the internals

mocksarebad.js

it("When a valid product is about to be deleted, ensure data access DAL was called once, with the right product and right config", async () => {

//Assume we already added a product

const dataAccessMock = sinon.mock(DAL);

//hmmm BAD: testing the internals is actually our main goal here, not just a side-effecr

dataAccessMock.expects("deleteProduct").once().withArgs(DBConfig, theProductWeJustAdded, true, false);

new ProductService().deletePrice(theProductWeJustAdded);

mock.verify();

});

Doing It Right Example: spies are focused on testing the requirements but as a side-effect are unavoidably touching to the internals

spies.js

it("When a valid product is about to be deleted, ensure an email is sent", async () => {

//Assume we already added here a product

const spy = sinon.spy(Emailer.prototype, "sendEmail");

new ProductService().deletePrice(theProductWeJustAdded);

//hmmm OK: we deal with internals? Yes, but as a side effect of testing the requirements (sending an email)

});

6. Don’t “foo”, use realistic input data

Do: Often production bugs are revealed under some very specific and surprising input — the more realistic the test input is, the greater the chances are to catch bugs early. Use dedicated libraries like Faker to generate pseudo-real data that resembles the variety and form of production data. For example, such libraries will generate random yet realistic phone numbers, usernames, credit card, company names, and even ‘lorem ipsum’ text. Consider even importing real data from your production environment and use in your tests. Want to take it to the next level? see next bullet (property-based testing)

Otherwise: All your development testing will falsely seem green when you use synthetic inputs like “Foo” but then production might turn red when a hacker passes-in a nasty string like “@3e2ddsf . ##’ 1 fdsfds . fds432 AAAA”

Anti-Pattern Example: A test suite that passes due to non-realistic data

nonrealisticdata.js

const addProduct = (name, price) =>{

const productNameRegexNoSpace = /^\S*$/;//no white-space allowd

if(!productNameRegexNoSpace.test(name))

return false;//this path never reached due to dull input

//some logic here

return true;

};

it("Wrong: When adding new product with valid properties, get successful confirmation", async () => {

//The string "Foo" which is used in all tests never triggers a false result

const addProductResult = addProduct("Foo", 5);

expect(addProductResult).to.be.true;

//Positive-false: the operation succeeded because we never tried with long

//product name including spaces

});

Doing It Right Example: Randomizing realistic input

realistic.js

it("Better: When adding new valid product, get successful confirmation", async () => {

const addProductResult = addProduct(faker.commerce.productName(), faker.random.number());

//Generated random input: {'Sleek Cotton Computer', 85481}

expect(addProductResult).to.be.true;

//Test failed, the random input triggered some path we never planned for.

//We discovered a bug early!

});

7. Test many input combinations using Property-based testing

Do: Typically we choose a few input samples for each test. Even when the input format resembles real-world data (see bullet ‘Don’t foo’), we cover only a few input combinations (method(‘’, true, 1), method(“string” , false” , 0)), However, in production, an API that is called with 5 parameters can be invoked with thousands of different permutations, one of them might render our process down (see Fuzz Testing). What if you could write a single test that sends 1000 permutations of different inputs automatically and catches for which input our code fails to return the right response? Property-based testing is a technique that does exactly that: by sending all the possible input combinations to your unit under test it increases the serendipity of finding a bug. For example, given a method — addNewProduct(id, name, isDiscount) — the supporting libraries will call this method with many combinations of (number, string, boolean) like (1, “iPhone”, false), (2, “Galaxy”, true). You can run property-based testing using your favorite test runner (Mocha, Jest, etc) using libraries like js-verify or testcheck (much better documentation). Update: Nicolas Dubien suggests in the comments below to checkout fast-check which seems to offer some additional features and also to be actively maintained

Otherwise: Unconsciously, you choose the test inputs that cover only code paths that work well. Unfortunately, this decreases the efficiency of testing as a vehicle to expose bugs

Doing It Right Example: Testing many input permutations with “mocha-testcheck”

pbt.js

require('mocha-testcheck').install();

const {expect} = require('chai');

const faker = require('faker');

describe('Product service', () => {

describe('Adding new', () => {

//this will run 100 times with different random properties

check.it('Add new product with random yet valid properties, always successful',

gen.int, gen.string, (id, name) => {

expect(addNewProduct(id, name).status).to.equal('approved');

});

})

});

8. Stay within the test: Minimize external helpers and abstractions

Do: By now, it’s probably obvious that I’m advocating for dead-simple tests: The team can’t afford another software project that demands a mental effort to understand the code. Michael Lync explains this in his great post:

**Good production code is well-factored; good test code is obvious…**When you write a test, think about the next developer who will see the test break. They don’t want to read your entire test suite, and they certainly don’t want to read a whole inheritance tree of test utilities.

Let the reader get the whole story without leaving the test, minimize utils, hooks, or any external effect on a test case. Too many repetitions and copy-pasting? OK, a test can leave with one external helper and stay obvious. But when it grows to three and four helpers and hooks it implies that it a complex structure is slowly forming

Otherwise: Suddenly found yourself with4 helpers per test suite, 2 of them inheriting from base util, a lot of setup and tearing-up hooks? congratulation, you just won another challenging project to maintain, you might write tests soon against your test suite

Anti-Pattern Example: Fancy and indirect test structure. Do you understand the test case without navigating to external dependencies?

indirect-test.js

test("When getting orders report, get the existing orders", () => {

const queryObject = QueryHelpers.getQueryObject(config.DBInstanceURL);

const reportConfiguration = ReportHelpers.getReportConfig();//What report config did we get? have to leave the test and read

userHelpers.prepareQueryPermissions(reportConfiguration);//what this one is doing? have to leave the test and read

const result = queryObject.query(reportConfiguration);

assertThatReportIsValid();//I wonder what this one does, have to leave the test and read

expect(result).to.be.an('array').that.does.include({id:1, productd:2, orderStatus:"approved"});

//how do we know this order exist? have to leave the test and check

})

Doing It Right Example: A test you may understand without hopping through different files

explicit-test.js

it("When getting orders report, get the existing orders", () => {

//This one hopefully is telling a direct and explicit story

const orderWeJustAdded = ordersTestHelpers.addRandomNewOrder();

const queryObject = newQueryObject(config.DBInstanceURL, queryOptions.deep, useCache:false);

const result = queryObject.query(config.adminUserToken, reports.orders, pageSize:200);

expect(result).to.be.an('array').that.does.include(orderWeJustAdded);

})

9. Avoid global test fixtures and seeds, add data per-test

Do: Going by the golden rule (bullet 0), each test should add and act on its own set of DB rows to prevent coupling and easily reason about the test flow. In reality, this is often violated by testers who seed the DB with data before running the tests (also known as ‘test fixture’) for the sake of performance improvement. While performance is indeed a valid concern — it can be mitigated (see “Component testing” bullet), however, test complexity is a much painful sorrow that should govern other considerations most of the time. Practically, make each test case explicitly add the DB records it needs and act only on those records. If performance becomes a critical concern — a balanced compromise might come in the form of seeding the only suite of tests that are not mutating data (e.g. queries)

Otherwise: Few tests fail, a deployment is aborted, our team is going to spend precious time now, do we have a bug? let’s investigate, oh no — it seems that two tests were mutating the same seed data

Anti Pattern Example: tests are not independent and rely on some global hook to feed global DB data

using-hooks.js

before(() => {

//adding sites and admins data to our DB. Where is the data? outside. At some external json or migration framework

await DB.AddSeedDataFromJson('seed.json');

});

it("When updating site name, get successful confirmation", async () => {

//I know that site name "portal" exists - I saw it in the seed files

const siteToUpdate = await SiteService.getSiteByName("Portal");

const updateNameResult = await SiteService.changeName(siteToUpdate, "newName");

expect(updateNameResult).to.be(true);

});

it("When querying by site name, get the right site", async () => {

//I know that site name "portal" exists - I saw it in the seed files

const siteToCheck = await SiteService.getSiteByName("Portal");

expect(siteToCheck.name).to.be.equal("Portal"); //Failure! The previous test change the name :[

});

Doing It Right Example: We can stay within the test, each test acts on its own set of data

independenttest.js

it("When updating site name, get successful confirmation", async () => {

//test is adding a fresh new records and acting on the records only

const siteUnderTest = await SiteService.addSite({

name: "siteForUpdateTest"

});

const updateNameResult = await SiteService.changeName(siteUnderTest, "newName");

expect(updateNameResult).to.be(true);

});

10. Don’t catch errors, expect them

Do: When trying to assert that some input triggers an error, it might look right to use try-catch-finally and assert that the catch clause was entered. The result is an awkward and verbose test case (example below) that hides the simple test intent and the result expectations

A more elegant alternative is the using the one-line dedicated Chai assertion: expect(method).to.throw (or in Jest: expect(method).toThrow()). It’s absolutely mandatory to also ensure the exception contains a property that tells the error type, otherwise given just a generic error the application won’t be able to do much rather than show a disappointing message to the user

Otherwise: It will be challenging to infer from the test reports (e.g. CI reports) what went wrong

Anti-pattern Example: A long test case that tries to assert the existence of error with try-catch

catch-in-test.js

it("When no product name, it throws error 400", async() => {

let errorWeExceptFor = null;

try {

const result = await addNewProduct({name:'nest'});}

catch (error) {

expect(error.code).to.equal('InvalidInput');

errorWeExceptFor = error;

}

expect(errorWeExceptFor).not.to.be.null;

//if this assertion fails, the tests results/reports will only show

//that some value is null, there won't be a word about a missing Exception

});

Doing It Right Example: A human-readable expectation that could be understood easily, maybe even by QA or technical PM

right-test-with-error.js

it.only("When no product name, it throws error 400", async() => {

expect(addNewProduct)).to.eventually.throw(AppError).with.property('code', "InvalidInput");

});

10. Tag your tests

Do: Different tests must run on different scenarios: quick smoke, IO-less, tests should run when a developer saves or commits a file, full end-to-end tests usually run when a new pull request is submitted, etc. This can be achieved by tagging tests with keywords like #cold #api #sanity so you can grep with your testing harness and invoke the desired subset. For example, this is how you would invoke only the sanity test group with Mocha: mocha — grep ‘sanity’

Otherwise: Running all the tests, including tests that perform dozens of DB queries, any time a developer makes a small change can be extremely slow and keeps developers away from running tests

Doing It Right Example: Tagging tests as ‘#cold-test’ allows the test runner to execute only fast tests (Cold===quick tests that are doing no IO and can be executed frequently even as the developer is typing)

tag-test.js

//this test is fast (no DB) and we're tagging it correspondigly

//now the user/CI can run it frequently

describe('Order service', function() {

describe('Add new order #cold-test #sanity', function() {

it('Scenario - no currency was supplied. Excpectation - Use the default currency #sanity', function() {

//code logic here

});

});

});

11. Other generic good testing hygiene

Do: _This post is focused on testing advice that is related to, or at least can be exemplified with Node JS._This bullet, however, groups few non-Node related tips that are well-known

Learn and practice TDD principles — they are extremely valuable for many but don’t get intimidated if they don’t fit your style, you’re not the only one. Consider writing the tests before the code in a red-green-refactor style, ensure each test checks exactly one thing, when you find a bug — before fixing write a test that will detect this bug in the future, let each test fail at least once before turning green, avoid any dependency on the environment (paths, OS, etc)

Otherwise: You‘ll miss pearls of wisdom that were collected for decades

Section : Test Types

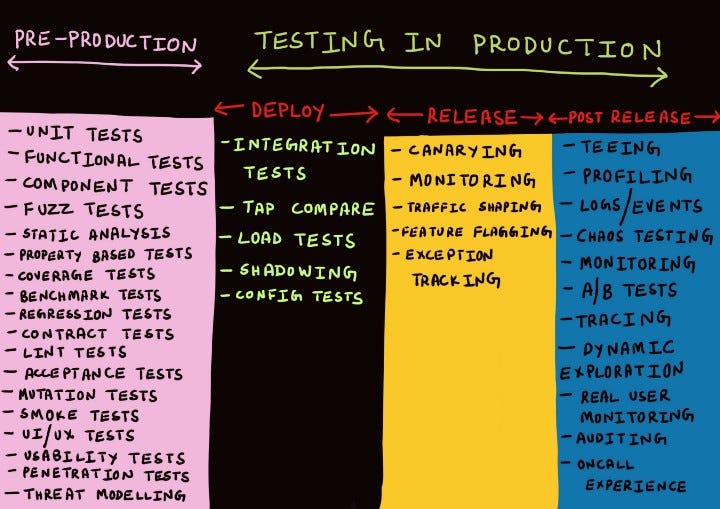

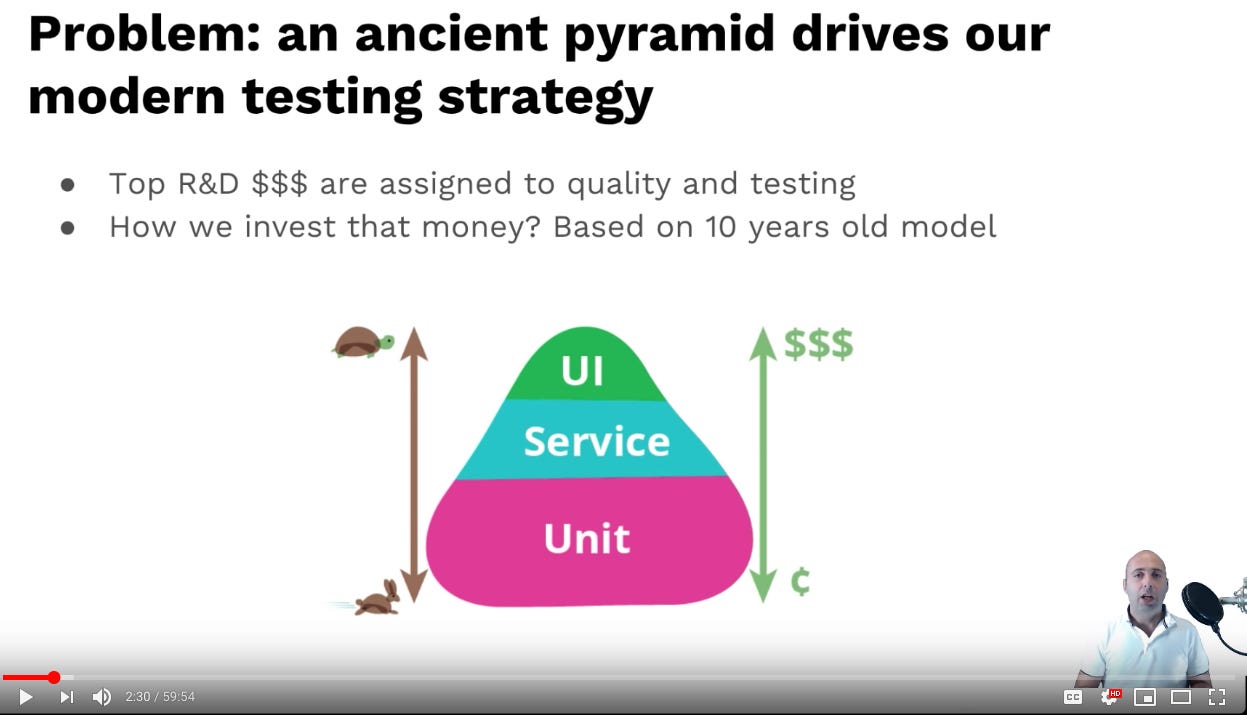

12. Enrich your testing portfolio: Look beyond unit tests and the pyramid

Do: The testing pyramid, though 10 years old, is a great and relevant model that suggests three testing types and influences most developers’ testing strategy. At the same time, more thana handful of shiny new testing techniques emerged and are hiding in the shadows of the testing pyramid. Given all the dramatic changes that we’ve seen in the recent 10 years (Microservices, cloud, serverless), is it even possible that one quite-old model will suit all types of applications? shouldn’t the testing world consider welcoming new testing techniques?

Don’t get me wrong, in 2019 the testing pyramid, TDD and unit tests are still a powerful technique and are probably the best match for many applications. Only like any other model, despite its usefulness, it must be wrong sometimes. For example, consider an IOT application that ingests many events into a message-bus like Kafka/RabbitMQ, which then flow into some data-warehouse and are eventually queried by some analytics UI. Should we really spend 50% of our testing budget on writing unit tests for an application that is integration-centric and has almost no logic? As the diversity of application types increase (bots, crypto, Alexa-skills) greater are the chances to find scenarios where the testing pyramid is not the best match.

It’s time to enrich your testing portfolio and become familiar with more testing types (the next bullets suggest few ideas), mind models like the testing pyramid but also match testing types to real-world problems that you’re facing (‘Hey, our API is broken, let’s write consumer-driven contract testing!’), diversify your tests like an investor that build a portfolio based on risk analysis — assess where problems might arise and match some prevention measures to mitigate those potential risks

A word of caution: the TDD argument in the software world takes a typical false-dichotomy face, some preach to use it everywhere, others think it’s the devil. Everyone who speaks in absolutes is wrong :]

Otherwise: You’re going to miss some tools with amazing ROI, some like Fuzz, lint, and mutation can provide value in 10 minutes

Doing It Right Example: Cindy Sridharan suggests a rich testing portfolio in her amazing post ‘Testing Microservices — the sane way’

Example: YouTube: “Beyond Unit Tests: 5 Shiny Node.JS Test Types (2018)” (Yoni Goldberg)

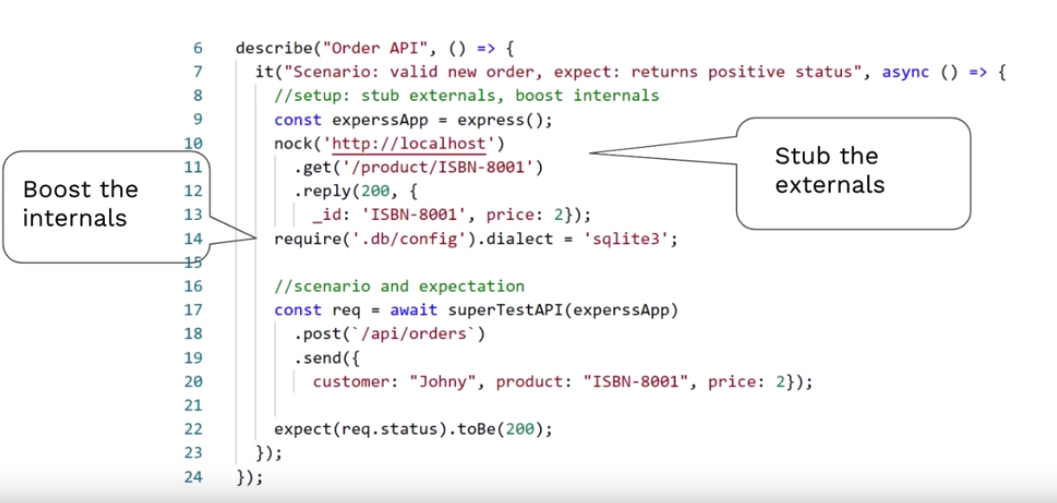

13. Component testing might be your best affair

Do: Each unit test covers a tiny portion of the application and it’s expensive to cover the whole, whereas end-to-end testing easily covers a lot of ground but is flaky and slower, why not apply a balanced approach and write tests that are bigger than unit tests but smaller than end-to-end testing? Component testing is the unsung song of the testing world — they provide the best from both worlds: reasonable performance and a possibility to apply TDD patterns + realistic and great coverage.

Component tests focus on the Microservice ‘unit’, they work against the API, don’t mock anything which belongs to the Microservice itself (e.g. real DB, or at least the in-memory version of that DB) but stub anything that is external like calls to other Microservices. By doing so, we test what we deploy, approach the app from outwards to inwards and gain great confidence in a reasonable amount of time.

Otherwise: You may spend long days on writing unit tests to find out that you got only 20% system coverage

Doing It Right Example: Supertest allows approaching Express API in-process (fast and cover many layers)

14. Ensure new releases don’t break the API using consumer-driven contracts

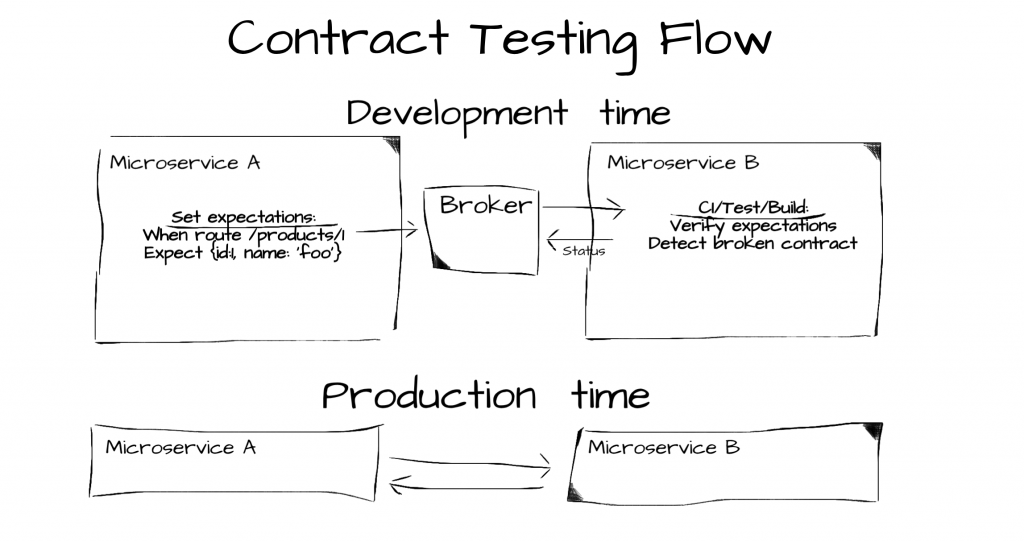

Do: So your Microservice has multiple clients, and you run multiple versions of the service for compatibility reasons (keeping everyone happy). Then you change some field and ‘boom!’, some important client who relies on this field is angry. This is the Catch-22 of the integration world: It’s very challenging for the server side to consider all the multiple client expectations — On the other hand, the clients can’t perform any testing because the server controls the release dates. Consumer-driven contracts and the framework PACT were born to formalize this process with a very disruptive approach — not the server defines the test plan of itself rather the client defines the tests of the… server! PACT can record the client expectation and put in a shared location, “broker”, so the server can pull the expectations and run on every build using PACT library to detect broken contracts — a client expectation that is not met. By doing so, all the server-client API mismatches are caught early during build/CI and might save you a great deal of frustration

Otherwise: The alternatives are exhausting manual testing or deployment fear

Doing It Right Example:

15. Test your middlewares in isolation

Do: Many avoid Middleware testing because they represent a small portion of the system and require a live Express server. Both reasons are wrong — Middlewares are small but affect all or most of the requests and can be tested easily as pure functions that get {req,res} JS objects. To test a middleware function one should just invoke it and spy (using Sinon for example) on the interaction with the {req,res} objects to ensure the function performed the right action. The library node-mock-http takes it even further and factors the {req,res} objects along with spying on their behavior. For example, it can assert whether the http status that was set on the res object matches the expectation (See example below)

Otherwise: A bug in Express middleware === a bug in all or most requests

Doing It Right Example: Testing middleware in isolation without issuing network calls and waking-up the entire Express machine

middleware-test.js

//the middleware we want to test

const unitUnderTest = require('./middleware')

const httpMocks = require('node-mocks-http');

//Jest syntax, equivelant to describe() & it() in Mocha

test('A request without authentication header, should return http status 403', () => {

const request = httpMocks.createRequest({

method: 'GET',

url: '/user/42',

headers: {

authentication: ''

}

});

const response = httpMocks.createResponse();

unitUnderTest(request, response);

expect(response.statusCode).toBe(403);

});

16. Measure and refactor using static analysis tools

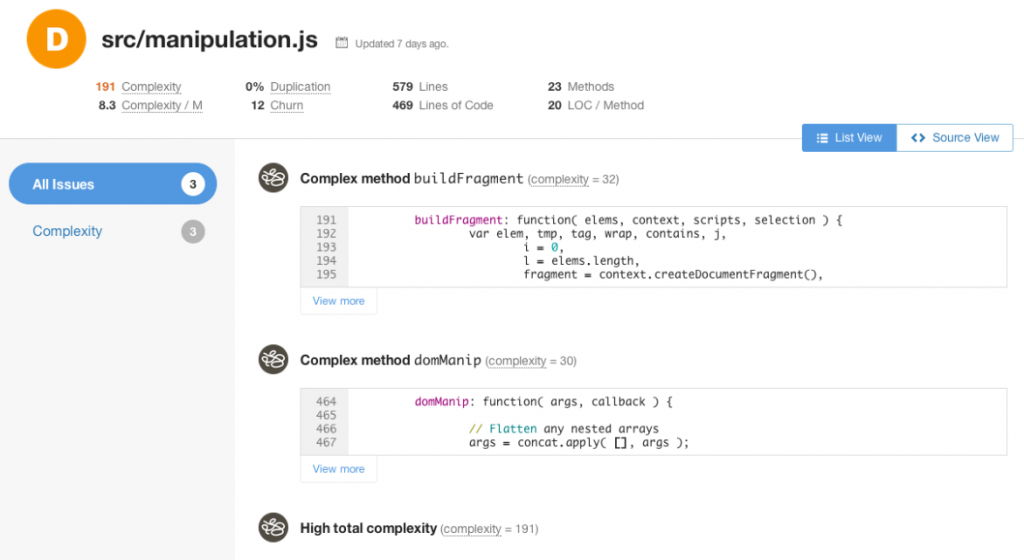

Do: Using static analysis tools helps by giving objective ways to improve code quality and keep your code maintainable. You can add static analysis tools to your CI build to abort when it finds code smells. Its main selling points over plain linting are the ability to inspect quality in the context of multiple files (e.g. detect duplications), perform advanced analysis (e.g. code complexity) and follow the history and progress of code issues. Two examples of tools you can use are Sonarqube (2,600+ stars) and Code Climate (1,500+ stars)

Credit: Keith Holliday

Otherwise: With poor code quality, bugs and performance will always be an issue that no shiny new library or state of the art features can fix

Doing It Right Example: CodeClimat, a commercial tool that can identify complex methods:

17. Check your readiness for Node-related chaos

Do: Weirdly, most software testings are about logic & data only, but some of the worst things that happen (and are really hard to mitigate ) are infrastructural issues. For example, did you ever test what happens when your process memory is overloaded, or when the server/process dies, or does your monitoring system realizes when the API becomes 50% slower?. To test and mitigate these type of bad things — Chaos engineering was born by Netflix. It aims to provide awareness, frameworks and tools for testing our app resiliency for chaotic issues. For example, one of its famous tools, the chaos monkey, randomly kills servers to ensure that our service can still serve users and not relying on a single server (there is also a Kubernetes version, kube-monkey, that kills pods). All these tools work on the hosting/platform level, but what if you wish to test and generate pure Node chaos like check how your Node process copes with uncaught errors, unhandled promise rejection, v8 memory overloaded with the max allowed of 1.7GB or whether your UX stays satisfactory when the event loop gets blocked often? to address this I’ve written, node-chaos (alpha) which provides all sort of Node-related chaotic acts

Otherwise: No escape here, Murphy’s law will hit your production without mercy

Doing It Right Example: Node-chaos can generate all sort of Node.js pranks so you can test how resilience is your app to chaos

Section : Measuring Test Effectiveness

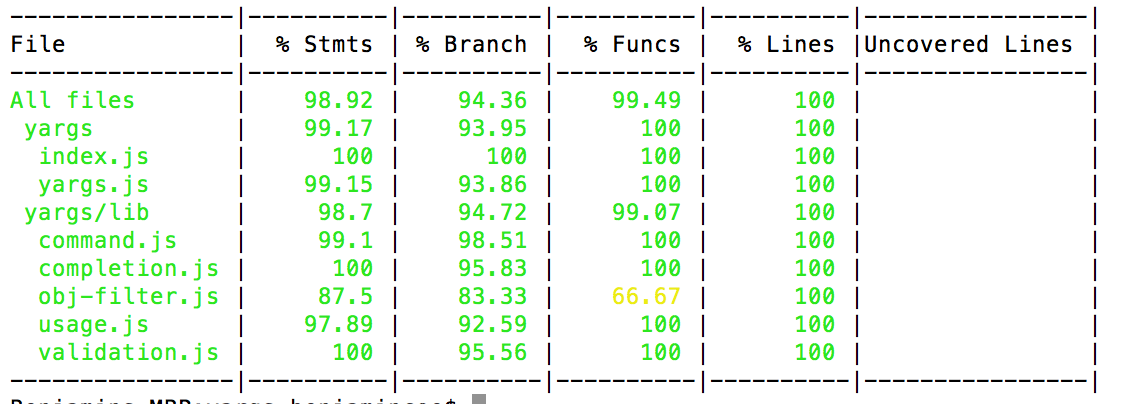

18. Get enough coverage for being confident, ~80% seems to be the lucky number

Do: The purpose of testing is to get enough confidence for moving fast, obviously the more code is tested the more confident the team can be. Coverage is a measure of how many code lines (and branches, statements, etc) are being reached by the tests. So how much is enough? 10–30% is obviously too low to get any sense about the build correctness, on the other side 100% is very expensive and might shift your focus from the critical paths to the exotic corners of the code. The long answer is that it depends on many factors like the type of application — if you’re building the next generation of Airbus A380 than 100% is a must, for a cartoon pictures website 50% might be too much. Although most of the testing enthusiasts claim that the right coverage threshold is contextual, most of them also mention the number 80% as a thumb of a rule (Fowler: “in the upper 80s or 90s”) that presumably should satisfy most of the applications.

Implementation tips: You may want to configure your continuous integration (CI) to have a coverage threshold (Jest link) and stop a build that doesn’t stand to this standard (it’s also possible to configure threshold per component, see code example below). On top of this, consider detecting build coverage decrease (when a newly committed code has less coverage) — this will push developers raising or at least preserving the amount of tested code. All that said, coverage is only one measure, a quantitative based one, that is not enough to tell the robustness of your testing. And it can also be fooled as illustrated in the next bullets

Otherwise: Confidence and numbers go hand in hand, without really knowing that you tested most of the system — there will also be some fear. and fear will slow you down

Example: A typical coverage report

Doing It Right Example: Setting up coverage per component (using Jest)

19. Inspect coverage reports to detect untested areas and other oddities

Do: Some issues sneak just under the radar and are really hard to find using traditional tools. These are not really bugs but more of surprising application behavior that might have a severe impact. For example, often some code areas are never or rarely being invoked — you thought that the ‘PricingCalculator’ class is always setting the product price but it turns out it is actually never invoked although we have 10000 products in DB and many sales… Code coverage reports help you realize whether the application behaves the way you believe it does. Other than that, it can also highlight which types of code is not tested — being informed that 80% of the code is tested doesn’t tell whether the critical parts are covered. Generating reports is easy — just run your app in production or during testing with coverage tracking and then see colorful reports that highlight how frequent each code area is invoked. If you take your time to glimpse into this data — you might find some gotchas

Otherwise: If you don’t know which parts of your code are left un-tested, you don’t know where the issues might come from

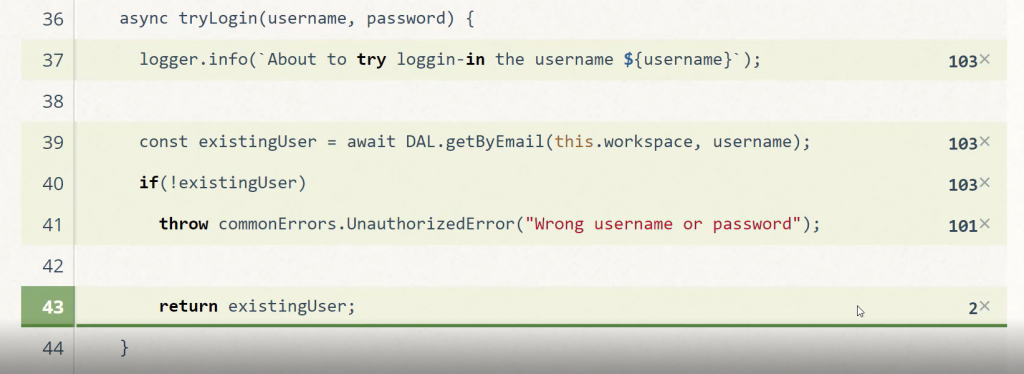

Anti-Pattern Example: What’s wrong with this coverage report? based on a real-world scenario where we tracked our application usage in QA and find out interesting login patterns (Hint: the amount of login failures is non-proportional, something is clearly wrong. Finally it turned out that some frontend bug keeps hitting the backend login API)

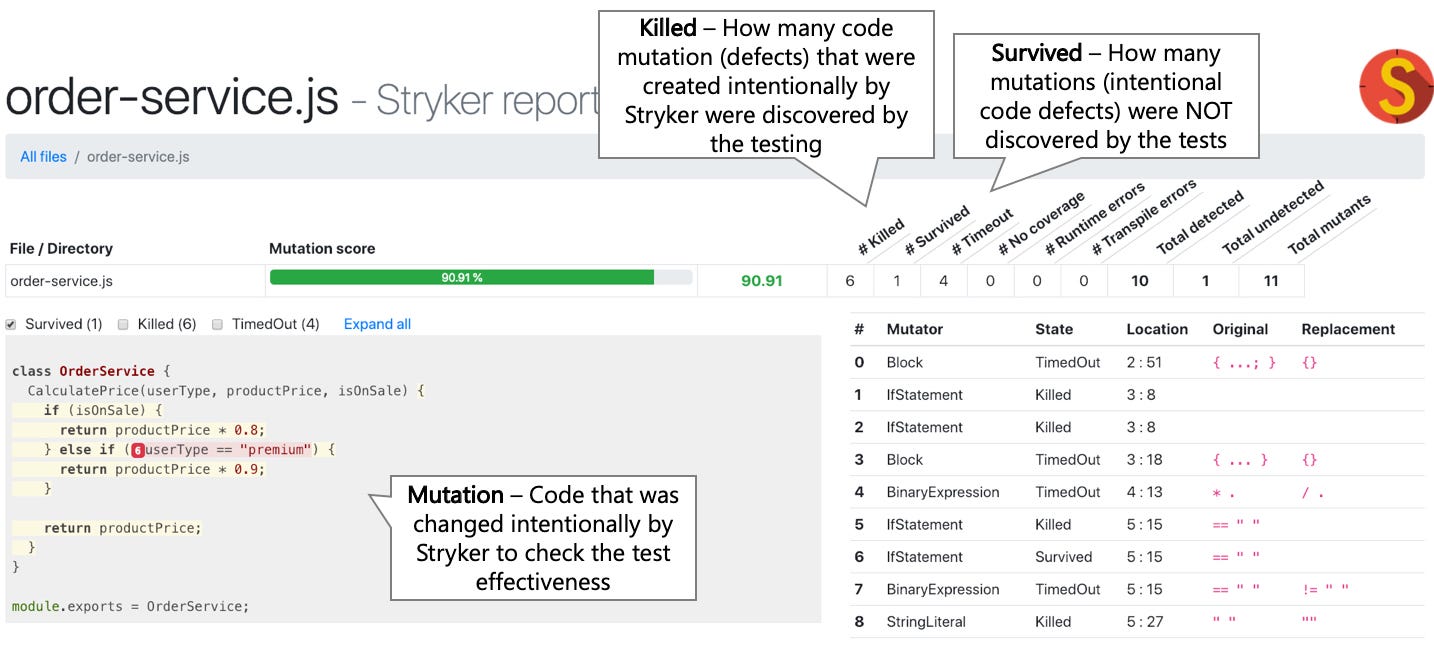

20. Measure logical coverage using mutation testing

Do: The Traditional Coverage metric often lies: It may show you 100% code coverage, but none of your functions, even not one, return the right response. How come? it simply measures over which lines of code the test visited, but it doesn’t check if the tests actually tested anything — asserted for the right response. Like someone who’s traveling for business and showing his passport stamps — this doesn’t prove any work done, only that he visited few airports and hotels.

Mutation-based testing is here to help by measuring the amount of code that was actually TESTED not just VISITED. Stryker is a JavaScript library for mutation testing and the implementation is really neat:

(1) it intentionally changes the code and “plants bugs”. For example the code newOrder.price===0 becomes newOrder.price!=0. This “bugs” are called mutations

(2) it runs the tests, if all succeed then we have a problem — the tests didn’t serve their purpose of discovering bugs, the mutations are so-called survived. If the tests failed, then great, the mutations were killed.

Knowing that all or most of the mutations were killed gives much higher confidence than traditional coverage and the setup time is similar

Otherwise: You’ll be fooled to believe that 85% coverage means your test will detect bugs in 85% of your code

Anti Pattern Example: 100% coverage, 0% testing

false-coverage.js

function addNewOrder(newOrder) {

logger.log(`Adding new order ${newOrder}`);

DB.save(newOrder);

Mailer.sendMail(newOrder.assignee, `A new order was places ${newOrder}`);

return {approved: true};

}

it("Test addNewOrder, don't use such test names", () => {

addNewOrder({asignee: "[email protected]",price: 120});

});//Triggers 100% code coverage, but it doesn't check anything

Doing It Right Example: Stryker reports, a tool for mutation testing, detects and counts the amount of code that is not tested (Mutations)

Section : CI & Other Quality Measures

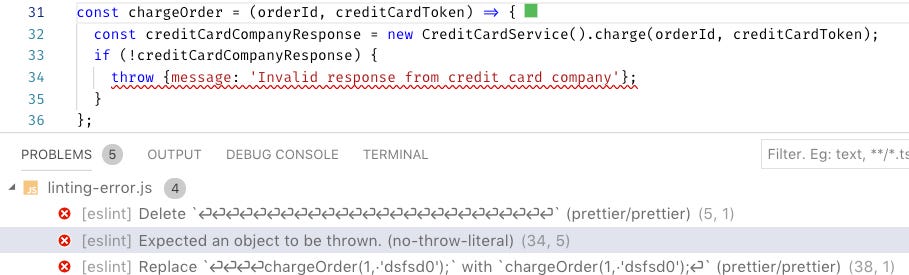

21. Enrich your linters and abort builds that have linting issues

Do: Linters are a free lunch, with 5 min setup you get for free an auto-pilot guarding your code and catching significant issue as you type. Gone are the days where linting was about cosmetics (no semi-colons!). Nowadays, Linters can catch severe issues like errors that are not thrown correctly and losing information. On top of your basic set of rules (like ESLint standard or Airbnb style), consider including some specializing Linters like eslint-plugin-chai-expect that can discover tests without assertions, eslint-plugin-promise can discover promises with no resolve (your code will never continue), eslint-plugin-security which can discover eager regex expressions that might get used for DOS attacks, and eslint-plugin-you-dont-need-lodash-underscore is capable of alarming when the code uses utility library methods that are part of the V8 core methods like Lodash._map(…)

Otherwise: Consider a rainy day where your production keeps crashing but the logs don’t display the error stack trace. What happened? Your code mistakenly threw a non-error object and the stack trace was lost, a good reason for banging your head against a brick wall. A 5min linter setup could detect this TYPO and save your day

Anti Pattern Example: The wrong Error object is thrown mistakenly, no stack-trace will appear for this error. Luckily, ESLint catches the next production bug

22. Shorten the feedback loop with local developer-CI

Do: Using a CI with shiny quality inspections like testing, linting, vulnerabilities check, etc? Help developers run this pipeline also locally to solicit instant feedback and shorten the feedback loop. Why? an efficient testing process constitutes many and iterative loops: (1) try-outs -> (2) feedback -> (3) refactor. The faster the feedback is, the more improvement iterations a developer can perform per-module and perfect the results. On the flip, when the feedback is late to come fewer improvement iterations could be packed into a single day, the team might already move forward to another topic/task/module and might not be up for refining that module.

Practically, some CI vendors (Example: CircleCI load CLI) allow running the pipeline locally. Some commercial tools like wallaby provide highly-valuable & testing insights as a developer prototype (no affiliation). Alternatively, you may just add npm script to package.json that runs all the quality commands (e.g. test, lint, vulnerabilities) — use tools like concurrently for parallelization and non-zero exit code if one of the tools failed. Now the developer should just invoke one command — e.g. ‘npm run quality’ — to get instant feedback. Consider also aborting a commit if the quality check failed using a githook (husky can help)

Otherwise: When the quality results arrive the day after the code, testing doesn’t become a fluent part of development rather an after the fact formal artifact

Doing It Right Example: npm scripts that perform code quality inspection, all are run in parallel on demand or when a developer is trying to push new code

local-ci.json

"scripts": {

"inspect:sanity-testing": "mocha **/**--test.js --grep \"sanity\"",

"inspect:lint": "eslint .",

"inspect:vulnerabilities": "npm audit",

"inspect:license": "license-checker --failOn GPLv2",

"inspect:complexity": "plato .",

"inspect:all": "concurrently -c \"bgBlue.bold,bgMagenta.bold,yellow\" \"npm:inspect:quick-testing\" \"npm:inspect:lint\" \"npm:inspect:vulnerabilities\" \"npm:inspect:license\""

},

"husky": {

"hooks": {

"precommit": "npm run inspect:all",

"prepush": "npm run inspect:all"

}

}

23. Perform e2e testing over a true production-mirror

Do: End to end (e2e) testing are the main challenge of every CI pipeline — creating an identical ephemeral production mirror on the fly with all the related cloud services can be tedious and expensive. Finding the best compromise is your game: Docker-compose allows crafting isolated dockerized environment with identical containers using a single plain text file but the backing technology (e.g. networking, deployment model) is different from real-world productions. You may combine it with ‘AWS Local’ to work with a stub of the real AWS services. If you went serverless multiple frameworks like serverless and AWS SAM allows the local invocation of Faas code.

The huge Kubernetes eco-system is yet to formalize a standard convenient tool for local and CI-mirroring though many new tools are launched frequently. One approach is running a ‘minimized-Kubernetes’ using tools like Minikube and MicroK8s which resemble the real thing only come with less overhead. Another approach is testing over a remote ‘real-Kubernetes’, some CI providers (e.g. Codefresh) has native integration with Kubernetes environment and make it easy to run the CI pipeline over the real thing, others allow custom scripting against a remote Kubernetes.

Otherwise: Using different technologies for production and testing demands maintaining two deployment models and keeps the developers and the ops team separated

Example: a CI pipeline that generates Kubernetes cluster on the fly (Credit: Dynamic-environments Kubernetes)

deploy:

stage: deploy

image: registry.gitlab.com/gitlab-examples/kubernetes-deploy

script:

- ./configureCluster.sh $KUBE_CA_PEM_FILE $KUBE_URL $KUBE_TOKEN

- kubectl create ns $NAMESPACE

- kubectl create secret -n $NAMESPACE docker-registry gitlab-registry --docker-server="$CI_REGISTRY" --docker-username="$CI_REGISTRY_USER" --docker-password="$CI_REGISTRY_PASSWORD" --docker-email="$GITLAB_USER_EMAIL"

- mkdir .generated

- echo "$CI_BUILD_REF_NAME-$CI_BUILD_REF"

- sed -e "s/TAG/$CI_BUILD_REF_NAME-$CI_BUILD_REF/g" templates/deals.yaml | tee ".generated/deals.yaml"

- kubectl apply --namespace $NAMESPACE -f .generated/deals.yaml

- kubectl apply --namespace $NAMESPACE -f templates/my-sock-shop.yaml

environment:

name: test-for-ci

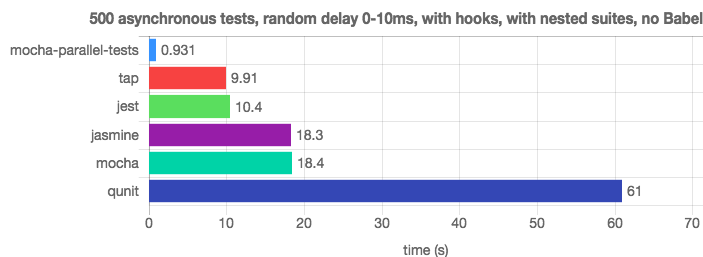

24. Parallelize test execution

Do: When done right, testing is your 24/7 friend providing almost instant feedback. In practice, executing 500 CPU-bounded unit test on a single thread can take too long. Luckily, modern test runners and CI platforms (like Jest, AVA and Mocha extensions) can parallelize the test into multiple processes and achieve significant improvement in feedback time. Some CI vendors do also parallelize tests across containers (!) which shortens the feedback loop even further. Whether locally over multiple processes, or over some cloud CLI using multiple machines — parallelizing demand keeping the tests autonomous as each might run on different processes

Otherwise: Getting test results 1 hour long after pushing new code, as you already code the next features, is a great recipe for making testing less relevant

Doing It Right Example: Mocha parallel & Jest easily outrun the traditional Mocha thanks to testing parallelization (Credit: JavaScript Test-Runners Benchmark)

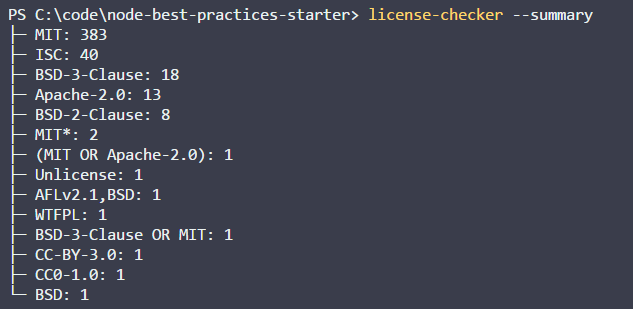

25. Stay away from legal issues using license and plagiarism check

Do: Licensing and plagiarism issues are probably not your main concern right now, but why not tick this box as well in 10 minutes?A bunch of npm packages like license check and plagiarism check (commercial with free plan) can be easily baked into your CI pipeline and inspect for sorrows like dependencies with restrictive licenses or code that was copy-pasted from Stackoverflow and apparently violates some copyrights

Otherwise: Unintentionally, developers might use packages with inappropriate licenses or copy paste commercial code and run into legal issues

Doing It Right Example:

//install license-checker in your CI environment or also locally

npm install -g license-checker

//ask it to scan all licenses and fail with exit code other than 0 if it found unauthorized license. The CI system should catch this failure and stop the build

license-checker --summary --failOn BSD

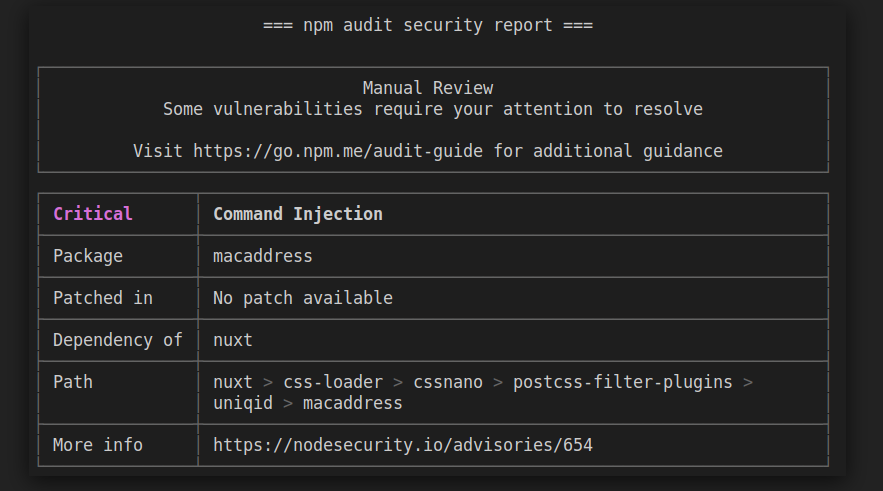

26. Constantly inspect for vulnerable dependencies

Do: Even the most reputable dependencies such as Express have known vulnerabilities. This can get easily tamed using community tools such as npm audit, or commercial tools like snyk (offer also a free community version). Both can be invoked from your CI on every build

Otherwise: Keeping your code clean from vulnerabilities without dedicated tools will require to constantly follow online publications about new threats. Quite tedious

Example: NPM Audit results

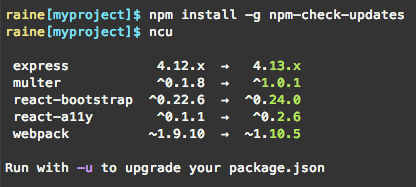

27. Automate dependency updates

Do: Yarn and npm latest introduction of package-lock.json introduced a serious challenge (the road to hell is paved with good intentions) — by default now, packages are no longer getting updates. Even a team running many fresh deployments with ‘npm install’ & ‘npm update’ won’t get any new updates. This leads to subpar dependant packages versions at best or to vulnerable code at worst. Teams now rely on developers goodwill and memory to manually update the package.json or use tools like ncu manually. A more reliable way could be to automate the process of getting the most reliable dependency versions, though there are no silver bullet solutions yet there are two possible automation roads: (1) CI can fail builds that have obsolete dependencies — using tools like ‘npm outdated’ or ‘npm-check-updates (ncu)’ . Doing so will enforce developers to update dependencies. (2) Use commercial tools that scan the code and automatically send pull requests with updated dependencies. One interesting question remaining is what should be the dependency update policy — updating on every patch generates too many overhead, updating right when a major is released might point to an unstable version (many packages found vulnerable on the very first days after being released, see the eslint-scope incident). An efficient update policy may allow some ‘vesting period’ — let the code lag behind the @latest for some time and versions before considering the local copy as obsolete (e.g. local version is 1.3.1 and repository version is 1.3.8)

Otherwise: Your production will run packages that have been explicitly tagged by their author as risky

Example: ncu can be used manually or within a CI pipeline to detect to which extent the code lag behind the latest versions

28. Other, non-Node related, CI tips

Do: _This post is focused on testing advice that is related to, or at least can be exemplified with Node JS._This bullet, however, groups few non-Node related tips that are well-known

- Use a declarative syntax. This is the only option for most vendors but older versions of Jenkins allows using code or UI

- Opt for a vendor that has native Docker support

- Fail early, run your fastest tests first. Create a ‘Smoke testing’ step/milestone that groups multiple fast inspections (e.g. linting, unit tests) and provide snappy feedback to the code committer

- Make it easy to skim-through all build artifacts including test reports, coverage reports, mutation reports, logs, etc

- Create multiple pipelines/jobs for each event, reuse steps between them. For example, configure a job for feature branch commits and a different one for master PR. Let each reuse logic using shared steps (most vendors provide some mechanism for code reuse

- Never embed secrets in a job declaration, grab them from a secret store or from the job’s configuration

- Explicitly bump version in a release build or at least ensure the developer did so

- Build only once and perform all the inspections over the single build artifact (e.g. Docker image)

- Test in an ephemeral environment that doesn’t drift state between builds. Caching node_modules might be the only exception

Otherwise: You‘ll miss years of wisdom

29. Build matrix: Run the same CI steps using multiple Node versions

Do: Quality checking is about serendipity, the more ground you cover the luckier you get in detecting issues early. When developing reusable packages or running a multi-customer production with various configuration and Node versions, the CI must run the pipeline of tests over all the permutations of configurations. For example, assuming we use mySQL for some customers and Postgres for others — some CI vendors support a feature called ‘Matrix’ which allow running the suit of testing against all permutations of mySQL, Postgres and multiple Node version like 8, 9 and 10. This is done using configuration only without any additional effort (assuming you have testing or any other quality checks). Other CIs who doesn’t support Matrix might have extensions or tweaks to allow that

Otherwise: So after doing all that hard work of writing testing are we going to let bugs sneak in only because of configuration issues?

Example: Using Travis (CI vendor) build definition to run the same test over multiple Node versions

language: node_js

node_js:

- "7"

- "6"

- "5"

- "4"

install:

- npm install

script:

- npm run test

Thank You. Other articles you might like

☞ Learn Nodejs by building 12 projects

☞ Supreme NodeJS Course - For Beginners

☞ Node.js for beginners, 10 developed projects, 100% practical

☞ Node.js - From Zero to Web App

☞ Typescript Async/Await in Node JS with testing

Suggest:

☞ Test Driven Development with Angular

☞ Getting Closure on React Hooks

☞ JavaScript for React Developers | Mosh

☞ React + TypeScript : Why and How

☞ React Testing Tutorial with React Testing Library and Jest